Poetic yet difficult to grasp, plain wrong in some respects, brilliant and insightful in others. This issue is dedicated to the memory of Mario Tronti.

Table of Contents

1 Bulletin 2: Class and Capital in the Renewables Industry

2 Worker Inquiries and Reflections: View from Workers in the Industry

3 Danger, Injury, and Death

4 ACTU Renewable Energy Report: View from the Institutions of Labour

5 Renewable Industries and Price: View from Capital and the State

6 Theoretical and Material Considerations

6a Energy and Capitalism

6b What is a ‘Labour Crisis’?

6c Environmental Context and Limits

7 Appendix

7a Surface Conditions of Capitalism in Australia

7b Text of Renewable Sector Questionnaire

7c Sources

Bulletin #2: Class and Capital in the Renewables Industry

"Inquiry is never neutral. Inquiry is a political act…" — Clark McAllister, Karl Marx's Workers Inquiry (2022)

"the factory is a big, open book - you only have to read it, and you will understand what it is that ails you and what you have to do to change things for the better." — Przedswit, May Issue (1886)

Within a context of intensifying crises, so-called ‘green capital’ increasingly carries the hopes of those wishing to kickstart a new cycle of accumulation. While energy transition is proving to be a fraught project, renewable energy production and infrastructures, across Australia and the globe, are expanding. Renewable energy forms a core component of the plans of green capitalists in terms of energy production, manufacturing of materials, and the extraction of rare metals and other minerals necessary for renewable energy production. Efforts to develop accords between business, state, and labour, highlight the significance green capital holds for those seeking a unity of purpose in managing and overseeing a new cycle of capital accumulation in energy production.

The growing significance of renewable energy reflects changing dynamics of class struggle and composition – intra-class struggle between factions of capital, broader social struggles against ‘fossil capital’ aiming to address the climate crisis, and ongoing class struggles within energy and related sectors of the economy. One dimension of the ongoing energy crisis, in Australia and globally, lies in the ‘inability of any fraction of capitalist politics to ensure the reliability and price of energy necessary for capital accumulation in a way that maintains, facilitates and increases that very same accumulation’ (Eden, 2019). What we can see in the shifting politics around energy generation in Australia, and in tensions playing out between green and fossil capital, relates to the question of understanding contemporary class composition in Australia today.

In this bulletin we delve into the composition of the renewable energy sector in Australia. We critically analyse various reports from government, industry, and union bodies. To complement our analysis of the economic structures of the renewable energy sector we also consulted literature, reports and news articles about the ‘human’ aspect of the industry. This included looking at the Australian Council of Trade Union's (ACTU) 2020 Renewable Energy Report, hunting through national news, and consulting other industry bodies to find further reporting on injuries and other impacts upon workers. It must be stated that even as this bulletin will go to print, many of the statistics will be out of date. The renewable energy sector is developing at such a rapid rate that not only data but even technologies relevant today are redundant tomorrow. This field is at the frontline of capitalist innovation and thus sets a frantic pace of accumulation and recomposition.

What we consider to be most important in this bulletin is our first rudimentary experiments at workers inquiry. Class and Capital in Australia did this by developing an online survey and having face to face discussions with people we know and have met in the field, including frontline workers and union organisers. While we received less responses than we were hoping for, the experience itself was rewarding and we see it as a starting point to a practice we hope to pursue in further issues. One member of the editorial collective also works in the renewables industry, so reflections are inevitably coloured by their experience. It should also be noted that we only talked to electrical workers. While there are also jobs in manufacturing, administration, research, transportation and various other fields related to the industry, we chose to zero in on those specifically involved in constructing renewable energy infrastructure.

For us, the workers' inquiry is a political point. If we are to attempt even a rudimentary understanding of capitalist dynamics, then we should not only consult the empirical economic data but the practical reality, subjectivities, experiences and lives of workers in these industries. We hope that this might help us glean an insight into not only the plan of capital, but the contradictions in its development, the chokepoints of capitalist accumulation, and a hint of where struggles may yet emerge. We hope the inquiry can help with some initial sketches in understanding the antagonisms in the renewables sector.

We have structured this bulletin according to ‘viewpoints’. The opening section presents the renewables from the workers’ viewpoint, covering the inquiries and related issues. We offer reflections on the inquiry findings and we present some data on workplace injuries in the renewable sector. Following this we present viewpoints from the institutions of the labour movement, specifically via an engagement with a report from the ACTU. The third section looks at the viewpoint of capital and the State, where we consider issues related to capital intensity, price, and the State. Finally, we present some theoretical and material considerations on the relationship between energy and capitalism, the meanings of a labour crisis, and considerations of the environmental context in which all the above issues are playing out. We hope this bulletin will contribute to further developing a critique of the limits of green capital accumulation and the realities of class composition in these areas of the economy.

Worker Inquiries and Reflections: View of Workers on the Industry

This section will cover the workers’ inquiry we completed in writing this bulletin. The questions from the inquiry are available in the appendix.

All of our direct respondents were limited to the Solar industry. We did briefly talk to two workers in wind production, however they declined to fill out a survey. Nonetheless, the conversations were indicative of similar, if slightly different trends in that sector of renewables. We had respondents from Queensland, New South Wales and Victoria, but none from Tasmania, South Australia, Northern Territory or Western Australia. One of our respondents did however recently do what was effectively fly-in-fly-out work in South Australia on a solar and battery farm. All respondents were mid-30’s and below, besides the conversations we had with Electrical Trades Union (ETU) organisers. Our inquiries reflected a relatively homogeneous workforce; everyone was a tradesperson (no trades assistants or labourers filled out the inquiry), all were male, all had worked in renewables only 1-4 years, and all were between their mid 20s-30s. Some went straight into their trade from school, or had come from another trade.

This younger workforce reflects the generational gap of renewable energy. Older workers are largely absent from the sector, at least in terms of manual labour. They may be present in management positions, but even such roles seem to be filled by people roughly mid 30s-40s. This may be reflective of the intense nature of solar work. It involves a lot of heavy lifting (panels are often around 20kg each, plus their size means they easily catch wind), bending, climbing and perching on steep roofs and exposure to adverse weather. A lot of travel is required, with residential jobs in different locations nearly daily and large scale jobs often in regional locations or industrial estates. It is worth immediately pointing out that the generational gap impresses another feature on solar. Younger people are less likely to be or have been union members, and have rarely undertaken industrial action. There is a near complete absence of tradition and education around workplace organising, workers rights and standards and conditions.

Collective organising is also uncommon amongst smaller workforces. Solar companies often operate a team between 3-15 people, some medium sized companies directly employ 30 plus and RACV Solar in Victoria reportedly has over 200 employees. Workers we spoke to fit within the medium to small enterprise range.

Everyone we spoke to reported that their workplace had a good tradesperson to apprentice ratio. This is hardly a surprise however, as the use of apprentice labour on award rates is much cheaper than employing either qualified labour or even labourers. Apprentices, unlike labourers, can also do ‘skilled’ electrical work. Even in 2023, the award rate for junior first year apprentices is only $14.62 per hour, so it is easy to see why employers would keep up this ratio. Most residential solar teams consist of one qualified electrician and two apprentices. It is not uncommon for teams to complete one full system install a day. The labour required is quite demanding in order for businesses to keep afloat in a cut-throat market with low profit margins. Prior to government mandated safety improvements and improvements in electrical standards over the last 5 or so years teams could install 2-3 systems in a single day. Many of these systems subsequently had issues whether because of the quality of work or dodgy equipment. Between the natural monopolies in the energy market and the swarm of small businesses trying to cash in on the turn to renewable energy, there is a high rate of exploitation and intensity of labour. The workers we talked to seemed quite cognizant of these factors, yet reflected a contradictory relationship with their jobs. Firstly, the positive.

Everyone we spoke to reported that they found their work meaningful. There is an explicit and conscious association with installing renewable energy as a net good. Respondents literally answered that they saw their role as ‘saving the planet’ and one suggested that, as they understood the market, ‘every install I do the less big energy companies earn’. Unfortunately this is not true, but it is still indicative of an altruistic relationship with their labour. The small team size of labourers tends to encourage positive relationships between coworkers, reinforced by intense physical labour in a skilled profession. Everyone reported that, weather notwithstanding, they enjoyed working outdoors and seeing new environments. Anyone who can picture starting an install, standing on a roof overlooking a sunrise on the Australian coast might relate. A similar comment was made by the worker on wind farms we spoke too. High above the plains looking out of one of humanity's new colossal achievements in energy production. As mentioned above, the work in renewable installation can be strenuous, but it also keeps workers fit.

All tradespeople we spoke to reported a good quality of life provided by their industry. Everyone in solar was paid at least $50 an hour, however this seems to be reflective only of the people we spoke too. We know that this is definitely not the industry standard. Nor is it the result of industrial action or negotiations. What appears to be driving up wages in the sector is the lack of skilled labour available in an industry that is reasonably well-regulated (electrical in general) and being a protected trade. It is worth noting that the wind farm worker we spoke to was not making as much as electricians in solar reported.

In contrast to the solar electricians, apprentices reported that wages don't even keep up with the cost of living, and one reported that they were not even being paid the award rate properly (again, this is actually fairly common). Increasing numbers of apprentices across the trades in general are employed by agencies, meaning they are shipped around to different jobs. Income is reflective of the awards or contracts at the company they are hired out to, and the short term employment tends to mean they are taken advantage of and given the most menial, repetitive and boring tasks. These ‘labour hire apprenticeships’ might mean seeing more facets of the industry, but it certainly does not guarantee the development of technical skills.

When we asked workers if they thought their ‘pay and conditions’ were fair, only one answered yes. Given an acknowledged contrast between un-unionised, intense solar work and EBA conditions this isn’t surprising. Apprentices also reported dissatisfaction with the industry, recognising that the skills they learn are extremely limited and do not translate well to the rest of the electrical field. Many express concerns that they would not find employment outside of renewables based on their particular skills. These concerns were generally echoed by the qualified electricians, who have all had experience in other sectors where they often ‘learnt most of their skills.’

Large scale solar is also extremely repetitive. Workers can spend up to months doing repetitive tasks; wiring simple circuits, doing up cable ties, installing cable tray, laying panels. Much of this work is actually mechanical, not electrical. Even the installation of electric vehicle infrastructure is relatively simple electrical work and gives little insight into complex wiring or construction. So while all our respondents labelled their work as rewarding, they also identified it as quite repetitive.

When we asked ‘Do you worry about your trade being protected? Does automation or the use of unskilled labour mean less hours or a lower quality of work?’ responses varied from acknowledgement that there is a continuous use of unskilled labour to do illegal work to ‘solar is becoming high quality’ and therefore skills are demanded. These reflections seem to be reflective of the particular companies these workers were at. Larger companies are using ‘unskilled’ and backpacker labour, smaller ones focused on residential jobs require skilled installers and apprentices.

A further cost cutting practice that is common across the industry is reliance upon workers to provide their own tools and equipment for the work. As identified in the ACTU’s Renewable Energy Report, a high capital investment is usually required to start a renewables business, and employers will sometimes attempt to get into the market despite not having enough funds. Only workers at the very smallest company we spoke to reported that their employer provided all the tools and equipment required to do the job! Furthermore, work-personal life boundaries were crossed, as all workers were required to use a variety of electronic devices for commissioning and running their jobs. For a number this includes the use of their personal phones.

Anecdotally, the Class and Capital member who works in Renewables dealt with this exact issue during their own apprenticeship. Their employer texted their entire workforce one night that everyone was required to have a GPS tracking app on their own phone the very next day or ‘not to bother showing up anymore’. As it happened, the normally disparate teams were working together on a commercial job that week, and when workers met up the next day they all expressed outrage at the situation. Everyone refused to work, and after a long discussion voted on one co-worker to call the bosses and let them know everyone was refusing to work unless the bosses redacted the GPS tracking demand. The employers responded by hosting an all in meeting that evening, which ended in an awkward stalemate. Everyone returned to work the next day, but one by one workers began to comply with the employer's demand to use the app. Over the following 6 months, almost the entire staff quit. Only the C&C member was also a union member, and without immediate outside support or other strategic and class struggle motivated workers it seemed impossible to solidify the refusal or win concrete demands.

This brings us to the next point, how our interviewees reported on conflict resolution in the workforce. Amongst our respondents everyone reported dispersed responsibility for dealing with health and safety issues. There were no Health and Safety Representatives mentioned, and the standards often fell back on the diligence of the employer and managers to ensure staff were provided appropriate training, equipment, procedures and PPE. When there were bigger safety grievances, workers were most likely to call on government bodies like WorkSafe or state energy regulators. All workers suggested they believed that electrical and safety standards in renewables could be higher, but this was largely seen through a lens of standardisation and governmental or third party scrutiny. There was little discussion amongst workers of a role for the unions or workers self-organisation. This could be due to lack of (positive) experience with unions and workers organisation, but it is still telling of the current situation in the industry. Union membership is extremely low in renewables, and in solar in particular. So far as C&C are aware, there are literally no EBA Solar employers in the entire country. ETU organisers did tell us that some construction companies are starting to create small subdivisions to install solar on major projects in the cities, as previously un-unionised solar companies have been doing work on otherwise union dense construction sites. There have been some EBA’s in Wind, but a worker told us that companies like Vestas use clever business tactics to employ workers to subsidiary companies based on the specific wind farm, thus ‘fragmenting’ the workforce that essentially works for them.

We should note that of our respondents, a significant percentage were actually union members, but were usually alone in their workplace. What this then tells us is that those who are engaged with unions are more likely to be open to thinking through their industry and responsive to engagement with critical inquiry.

Reflections on the Inquiries

Though rudimentary, our first inquiries were a valuable exercise. The subjective reflections of workers, compiled with empirical data and analysis of tendencies in Australian, and global, capital, point to some interesting observations.

Workers in renewables tend to be younger than other sectors of the electrical industry, and are less likely to have experienced unionised work. Their wages are essentially determined by the market, that is employers need to pay a rate that attracts and maintains skilled workers willing to undertake and maintain the specific licences required to work in renewables.

Wages for apprentices however are unsustainable. Combining their low incomes with limited training it is unlikely that many apprentices see value in seeing out their apprenticeships with a single company. It will be interesting to see how this trend progresses as Australia becomes increasingly ‘electrified’. That is, more and more powered by renewables alone. Apprenticeships and jobs in renewables look very different to the generations before where a worker could theoretically get a life-time job at a coal-driven power station. As the Renewable Energy Report hints, the majority of jobs in renewables are in construction, but as Australia will inevitably reach electrification there will be the question of where these jobs go. Renewable energy production requires little in the way of maintenance. Will ageing renewable workers be forced to leave the industry by the physical nature and fast pace of the work? Or will this crystallise into an issue that they are forced to deal with, having a very specific set of skills that are not necessarily immediately applicable to other sectors of electrical work.

If the future of Australian energy production is centred on solar and wind farms and in hydropower, then the above factors might suggest a collapse of conditions for workers in the new power industry. Remote, insecure work that replaces previous generations' hard won EBA wages and conditions looms on the horizon.

The remoteness of renewables is a considerable factor. Capital will have to construct a ‘geography of accumulation’ that is largely outside the major cities. Just how the State will facilitate this is an open question, as Green Capital itself is unlikely to be able to fund the developments.

As capital is concentrated in cities, so too is labour organisation. The production of large-scale renewable energy tends to be remote, meaning the small crews of workers are often isolated from one another. This would tend to suggest workers organisation is less likely, though of course not impossible. In turn small scale production in the cities also tends to be so dispersed it is no different to small scale construction - nearly impossible to ‘organise.’

In the absence of acute struggle, there are limited resources dedicated to on-the-ground organising by the Electrical Trades Union (some branches being less proactive than others). The two factors above also suggest that any improvements will be purely the result of state regulation, market conditions or ‘informal’ activity by workers outside of the unions.

Unfortunately, workers in renewables currently seem to display a lack of class autonomy when it comes to their own health and safety, relying on company policies and procedures and maintaining faith in state institutions.

While wages in renewables may not be as low as sectors like residential construction, there are also few incentives. This is also seen in the incredible lack of skilled labour required for Australia to have even a remote possibility of achieving its climate ‘targets.’

Nonetheless, despite the sometimes laborious and intense nature of the work, renewables workers seem to be currently ideologically disposed towards supporting green capital, rather than shunting it off as they might do other ‘meaningless’ jobs. To a degree, they also see the renewables industry as in dispute with fossil capital (though our interviewees wouldn't frame it in these terms).

Danger, Injury and Death

One issue raised by our inquiry, where the respondent gave the example of falling from a roof, is that of safety.

As far back as 2012 there was an incident on a wind farm in Macarthur where a worker was injured by the blade of a wind turbine on a Vestas site (Recharge News, 2012). Within months a second worker was reported as injured by a falling object that left the employee with spinal injuries (Wind Power Monthly, 2022). Vestas, a Danish company, is a major player in global renewables with over 29,000 employees. They are one of the main contracting companies for the construction of wind farms in Australia.

In 2017 three workers at the New South Wales ‘White Rock’ Wind Farm were injured when their ute rolled 30 metres down an embankment. One had internal bleeding and was left with spinal injuries in an event that earned the ire of CFMEU organisers, who complained of unsafe practices of the contracting company Goldwind (Glen Innes Examiner, 2017).

In 2018 a Victorian worker was far less fortunate than our interviewee and fell from a single story roof to his death (Worksafe NSW, 2018).

In 2020 a man in Adelaide won a court case against an unnamed wind farm company after they attempted to cut off payments for injuries to his back in 2017 (The Advertiser, 2020).

In 2020 a SafeWork South Australia blitz across the solar industry identified 21 instances of non-compliance with safety standards. It was not enough to prevent three ‘serious injuries’ on different occasions nor two more the following year (Bloch, 2022). In 2022 SafeWork NSW also reported an incidence of an apprentice falling 4 metres from a roof and suffering ‘serious injuries’ (SafeWork, 2022). In March this year a decision was made to prosecute a Queensland employer after a worker in Hervey Bay fell from a ladder and sustained serious injuries in 2020.

The last incident we found a media report of was in 2021 when a NSW worker working for CWP Renewables at Bango Wind Farm in Lachlan Valley Way lost his hand (About Regional, 2021).

Media reports only give a small glimpse into what is happening. There are obviously more injuries that don't make it into the news, including the example of our inquiry participant. We also know of a worker who moved into a management role and died by suicide; reportedly ‘work stress’ a high driving factor.

The last few years have seen a number of ‘blitzes’ by state authorities attempting to intervene and ‘clean up’ the renewables industry. This includes rapid rewriting of electrical and safety standards to include the new industries. It seems the State itself is somewhat aware that at the beginnings of the renewable energy industry, they ‘let the horse bolt’ and are now playing catchup to a dangerous and under regulated industry. Beyond the dangers inherent in working with electricity or working at heights, there are risks in terms of long term exposure to silica contained in roof tiles and fairly common back injuries. So far as we are aware, there have been no studies on the impact of either of these on renewables workers.

The above sections have attempted to grasp some elements of how workers themselves relate to the renewable industry. In turn, we will look at the view from the perspective of the unions as institutions, state policy makers and the market.

ACTU Renewable Energy Report: View from the Institutions of Labour

In 2020 Michelle O’Niel and the ACTU released their ‘Renewable Energy Report’ (RER), the first study of its kind detailing the dynamics of Renewable Energy and what it means for Australian workers. (Australian Council of Trade Unions, 2020) As the report noted “Australia is experiencing a rapid, and at times chaotic, energy transition.” At the time, there was no national transitional plan or state body designated to manage the transition. In the years since the report, the Liberal government has been replaced by Labor and in the very time since we started researching renewables this has been turned around with the announcement of the new ‘Net Zero Authority’ (NZA). There have also been smaller scale reforms on state-based levels, at least in terms of regulation of safety, and electrical and installation standards.

The RER also noted that ‘despite this lack of national leadership Australia’s renewable energy industry has developed rapidly to become a major industry and employer, with at least 27,000 Australians employed in the sector, which could grow to 45,000 jobs by 2035. Yet many of these new jobs lack the security and conditions of the jobs at fossil fuel power stations and mines.’ This is because many of the jobs are in small-scale solar where regulation is hard to enforce and labour organisation is basically non-existent. In large-scale solar, conditions are also poor with consistent issues around the use of backpackers as labour.

The RER reports a number of key factors to why solar (and renewables in general) lag so far behind other sectors of the power and construction industries. These include capital intensity, offshore manufacturing, lack of coherent policy, and the interlinked ‘race to the bottom’ (competition), high turnover of companies (tendency towards centralisation) and also bemoans what is essentially a ‘lack of ethical business practices.’

While the ACTU’s bemoaning of ethical business is idealism that can be easily dismissed, their other points are pertinent. Renewable energy is still a relatively new industry whose birthing pains include being used as a political football by factions of the ruling class (not only politicians, but segments of capital with different visions). The up-and-down nature of state provided subsidies to the sector creates a fragility in the confidence of the capitalists who have chosen to invest. When substantial funding incentives can be instantly pulled by a new government, business owners remain conscious of the need to shore up their potential profits against a rapid shift in the industry.

Furthermore, the lack of consistent funding and projects has contributed to the small size of the businesses that form the majority of the industry. There simply has not been substantial enough work, particularly in the more cutthroat solar sector, for larger businesses to emerge. Similarly small businesses are built to cash in on periods of high government incentive and then disappear when funding dries up.

High turnover of business is thus inevitable, as less competitive capitals collapse and are replaced by new companies. There is a significant monopoly on major projects held by companies such as AGL allowing them to subcontract work out at tight margins. The swarm of smaller companies competing for the scraps from these corporate giants contributes further to downward pressure on business margins, and hence wages, conditions and standards. Even companies with ‘award winning records’ such as Victorian based ACLE openly advertise to employ backpackers and have had projects shut down by Energy Safe Victoria (ESV), a regulatory body that ensures national standards of electrical work.

Renewable Industries and Price: View from Capital and the State

Having considered the workers' inquiry responses, this section will cover some of the broad conditions of the renewable sector in Australia, before moving into a presentation of the mechanics of the energy market and prices.

The renewable energy sector consists primarily of solar, wind, and hydro energy production. While renewable energy has traditionally been sourced from wind and hydro, solar is expanding relatively rapidly. The main firms in the wind and hydro part of the industry are AGL, Iberdrola Australia, Hydro Tasmania, and Pacific Hydro. And in solar, Neoen Australia, FRV Australia, Wirsol Energy, AGL, and Enel Green Power Australia.

Taking wind and hydro as one section of the renewable energy sector, it employs over 3500 workers, and is forecast to keep growing over the next 5 years at a rate of 6.7%. The wage bill for the sector stands at $334.6 million in 2023. The growth in the wage bill has been a result of more wind farms coming online, and as such growing employment in the sector. According to IBIS World, the revenue across this section is $2.6 billion, growth of which is set to slow over the next 5 years to reach $2.7 billion by 2028. Of this figure, $553 million constitutes profit with a profit margin of 21%, expected to fall to 18.2% by 2028. This sector of the renewables industry has a high level of capital intensity, where as of 2023 “for every dollar spent on labour, industry operators spend an estimated $0.59 on capital investment” (Treisman, 2023a).

Turning our attention to solar energy production we see the following. Solar employs over 4000 workers, with a wage bill of $323.8 million. Revenue for the sector is at $1.5 billion, with profit share at $346.4 and a profit margin of 23.4%. The expansion of solar energy production in Australia, particularly as large-scale projects are attracting more investment, solar farm sizes increase, and output and economies of scale are sought (Triesman, 2023b).

The focus on national accounts, while providing some insight into what is happening on this continent at the moment, is also misleading. Capital, labour, value, and exploitation are global in character. One aspect of this we can point to which is relevant to the growth in renewables in Australia is the supply of renewable components. The concentration of the production of components of solar energy generation, particularly solar panels but also other photovoltaic technologies, in China has cheapened the costs of capital investment. China makes up over 80% of photovoltaic panel production across all stages of the manufacturing process (International Energy Agency, 2022), and is a primary manufacturer of wind turbines. Firms in China are responsible for the top 10 suppliers of solar photovoltaic equipment and materials and 7 of the top 10 manufacturers of wind turbine products, globally (McKinsey, 2023). This indicates that the rolling out of renewable infrastructures in Australia has relied in part upon large scale government subsidies, but also, like many places in the world, upon the manufacture of solar panels and wind turbines in China. While we have not been in a position to conduct worker inquiries in China, there have been several reported wage disputes in the renewable industries, from construction to the manufacturing of solar panels. These have primarily taken the form of unpaid wages and wage arrears struggles, as well as protests over industrial pollution arising from the production of these components (China Labour Bulletin, 2019; China Labour Bulletin, Strike Map).

Trends and Plans

The above tells us something about what we might call trends emerging in the renewables industry, but is there any indication of a plan from capital or the Australian state?

We need to grasp this in two ways.

Firstly, we understand that each firm acts as a capitalist firm. It invests with the aim of generating a profit. The actions it must take to accomplish this are imposed on it by the disciplinary effect of a competitive market. We recognise that conditions of monopoly or market dominance develop in energy markets, but this must be considered secondary to the operation of the market in general.

Secondly, we also wish to grasp how capital plans. By this we mean how the different segments and partisans of capital work politically in their effort to develop an understanding of the problems within capitalist society, and address them on their own terms.

In practice, many of these actors are not capitalists per se – i.e., they are not the direct owners, or even functionaries, of capital. Or if they are, they aren’t acting in their capacity as capitalists. We find that those who aim to plan for capital include the State, politicians, academics, journalists, NGOs, the union bureaucracy, think tanks, and so on. Frequently, these actors confront the problems of capitalism via the dominant framework of ideas; meaning, through the framework of ideology, or idealism. Much of what is called ‘politics’ in our society is, on closer examination, a conflict over the plan for capital. As such we have chosen to focus on a recent speech by the Australian Energy Market Operator (AEMO) CEO as a clear expression of the dominant plan of capital at this point in time. (AEMO, 2023)

Speaking at the Australian Clean Energy Summit in July 2023, the AEMO identified ‘four pillars’ for the energy transition:

Low-cost renewable energy like solar, wind and hydro.

Firming capacity to smooth out the peaks and troughs, like batteries, pumped hydro, and flexible gas generation.

New transmission and modernised distribution networks to connect consumers to those new sources of energy, and

Power systems capable of running, at times, entirely on renewable energy.

For the AEMO, the capacities of capital and the State to construct these pillars are hindered by inflation, global supply chain constraints, workforce constraints, across-the-board cost of living increases – including the cost of energy – and community reactions to large-scale energy projects.

As a result there is an initial frustration at the slow pace of energy transition. This is attributed to three sets of problems, or antagonisms:

Between today and tomorrow – that is, between the need to maintain energy supply in the present whilst shifting how energy is produced.

Between parts and whole – meaning, how to integrate the various kinds of generation and distribution, and

Between people and populations – the conflict between the need to generate energy for large populations in urban centres and the impact of this on rural communities where energy generation happens.

Implementing a successful transition is seen as a vast economic opportunity. The language of a shift to renewables being economically and strategically ‘good for Australia’ is the hegemonic position of the political centre.

The main weakness is the absence of sufficient investment in new renewables, despite their prediction that two thirds of coal generation will exit the market within seven years.

The AEMO then looks to various State and Federal schemes designed to make investment attractive and underwrite it. Their analysis suggests that they understand that profits are, under ‘normal’ conditions, not sufficient to attract capital. Profit margins of 21% in renewables still sit much lower than in coal, which has been reported at 26% (Ibis World, 2023), 45% (CFMEU), and increasing by up to 89% since 2019 (Stanford, 2023).1

On the other hand, the increase in renewable energy creates problems for the energy grid as a system. There is a requirement for ongoing and consistent energy generation. The AEMO is worried (contra right-wing paranoias) that renewables will create periodic spikes in generation that overwhelm the system. At the same time, however, they are working to speed up the connection time of new forms of generation to the grid.

The AEMO response is relatively threadbare: engaging early and proactively with project developers, equipment manufacturers, and network service providers to find agreement on critical project issues; allocation of responsibilities across all parties; and working on reports.

This represents, we think, the need for (but difficulty in achieving) some form of central planning within the market economy of a federated nation State.

To meet the potential conflicts arising from increased energy generation and transmission in rural areas, AEMO has formed a panel of ‘experienced farming, Traditional Owner, consumer and regional voices’ to identify concerns and establish forms of compensation for different regional interests. This includes organising face to face meetings in town halls to manage these issues.

All of this is framed as part of a ‘win-win ideology’ which highlights the social, economic and ecological benefits of the transition.

As antagonists to capital and the State, we understand such a statement as evidence of a plan that recognises the scale of the challenge faced by Australian capitalism. The planners of capital hope to manage this challenge through a mixture of State intervention (for the purposes of creating and guaranteeing markets), sustained investment, and the management of social dysfunction.

Analysis of Price

To better understand the conditions that capital is working within, a solid understanding of the fundamental market is required. Consumer energy prices have been drastically increasing. The two largest electricity retailers - Origin Energy and AGL - have a combined market share of ~50% and have recently announced price increases of between 21-30% for households in South-East Queensland, New South Wales, South Australia, and Victoria. (ABC News, 2023) These exorbitant price increases are combined with levels of inflation that haven’t been seen in generations. Given the centrality of electricity in the production and provision of goods and services, this will have a significant flow on effect. Therefore, it is crucial we understand what is driving these price increases.

Households generally interact with the electricity ‘market’ based on the retailer they choose. Different States and Territories have a differing degree of deregulation, with Victoria having the largest number of retailers, followed by NSW, SA, and South-East Qld. These retailers are effectively a billing agent and do not impact the electricity that actually flows from the network into homes and businesses. The physical and financial markets that underpin this are far more complex and require additional insight.

Physical Electricity Market

The National Electricity Market (NEM) covers the Eastern Seaboard and comprises various types of generators and over 43,000km of connected transmission lines. Each State has their own electricity market, however there are several interconnectors to compensate between States:

Tas ←→ Vic

Vic ←→ NSW

Vic ←→ SA

NSW ←→ Qld

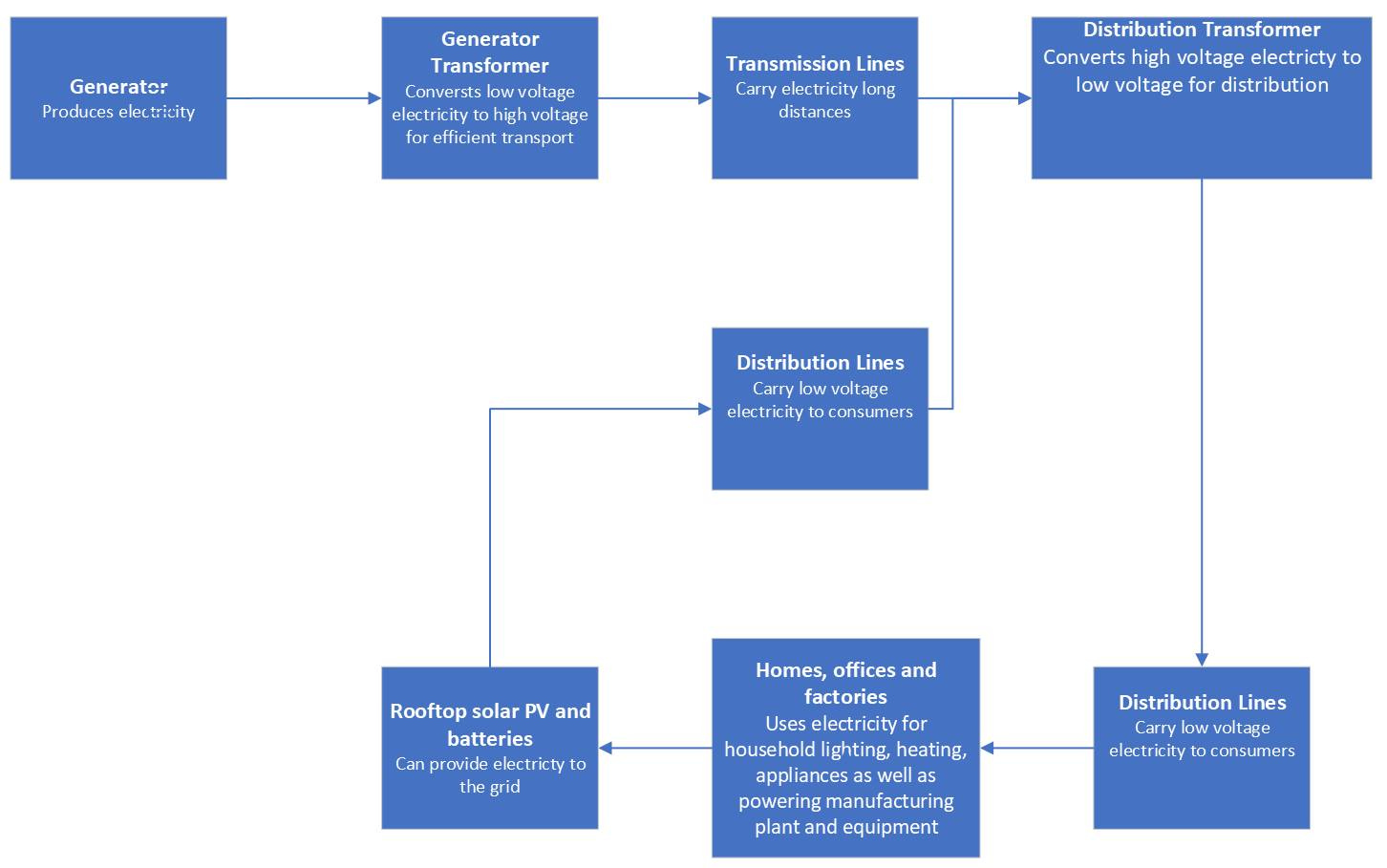

The NEM has over 500 registered participants, including market generators, transmission network service providers, and customers. $11.5 billion (AUD) was traded via the NEM in the financial year of 2020-21. Coal generation remains the dominant source of electricity generation across the NEM (64.67%), followed by Wind (10.45%) and Hydro (7.21%). Gas constitutes 6.57%. Regardless of how the energy is generated, the electricity is converted to high voltage to transport across large distances before it is converted back to low voltage for distribution.

(AEMO, 2021)

The ownership of these assets is significantly varied. Electricity generators were historically Government owned entities. Since the wave of privatisation the majority of generation capacity is privately owned by either Australian companies such as AGL and Origin Energy, or international conglomerates. However, the Queensland government maintains ownership of Stanwell Corporation, similarly the Tasmanian Government over Hydro Tasmania, and the Snowy Hydro Scheme is now entirely owned by the Federal Government.

Similarly, the Queensland and Tasmanian Governments maintain ownership of their transmission assets, those in other states are owned by international infrastructure companies. This is similarly the case with local distribution networks where there is a mixture of ownership. Crucially, these companies are natural monopolies as there is only one transmission or distribution operator in any one area. Therefore, these companies are effectively rent seeking operations which put minimal investment into their assets and seek maximum returns from the Australian Energy Regulator. These costs make up approximately 50% of an average household’s electricity bill, however, the recent increases have been driven by the wholesale electricity price.

The Physical and the Financial

Each state has their own market and every 5 minutes the generators will bid how much they will generate and at what price. The Australian Energy Market Operator (AEMO), manages this market by setting the price based on the lowest bids to cover the aggregate demand (Stanwell, 2022). Every generator who has been called upon to dispatch will be paid the same price and each retailer, based on their customers’ consumption, will pay that price. Average wholesale prices have been increasing over the past decade from ~$30-50/MWh to ~$100-150/MWh. However, this market is extremely volatile and prices can range from -$1,000/MWh to $15,500.MWh. A negative price event occurs when there is too much supply for the aggregate demand and large baseload generators will pay to keep generating as a more cost effective approach than temporarily shutting down. High price events generally occur during heat-waves and at peak periods, often impacted by either planned or unplanned outages.

Given the extreme volatility of these markets, retailers and generators will enter into financial derivative arrangements, to decrease their exposure to the wildly fluctuating prices. These financial products have differing degrees of sophistication, and while there is some transparency for the future contracts, many agreements are entered into off the public exchange and large retailers (Origin Energy, ALG, Energy Australia) are also large generators making the process more opaque. Large businesses that have high energy consumption will also enter into fixed term, fixed price contracts with retailers years in advance based on these futures contracts. We do know that futures contracts have been increasing over the past years, and we are now seeing some of those impacts. What’s driving these increases is less clear.

Price Increases

There are several reasons for why the wholesale prices have been increasing. Over recent years, thermal coal prices have risen considerably, from ~US$80/t at the beginning of 2021 to regularly ~US$350-450/t throughout 2022. Australia exports ~75-80% of the thermal coal mined domestically so even though the cost of mining coal has not significantly increased, the companies deemed they had an ‘opportunity’ to sell at a higher price, therefore impacting future contracts of electricity. Further, since Russia’s full scale invasion of Ukraine, prices for gas have also increased, and as Australian producers export the vast majority of gas through LNG, this added further pressure on the electricity market as gas generation still plays a significant role. We can see that while the fundamental costs of fossil fuels did not significantly increase, those in control of the resources saw an opportunity to increase profits and we are now seeing that impact in our everyday cost of living.

There have been several impacts from factors closer to home. Firstly, a number of base-load generation, particularly in Queensland, has had unplanned outages impacting the supply. However, crucially, a significant issue has been investment uncertainty based on the so-called “climate wars” (Crowley, 2021). This has resulted in a paradigm of ageing fossil fuel facilities being run into the ground, while limited new renewable investment is being undertaken. While Australia is still wedded to fossil fuels for electricity, and those assets are continuing to degrade, we are caught in a bind of being at the whim of international financial markets for resources, as well as a failure to adequately invest in renewable energy to put downward pressure on wholesale electricity prices.

6. Theoretical and Material Considerations

a) Energy and Capitalism

Debates about energy often pose the issue as essentially a technical question. You have different forms of energy generation; they have different kinds of inputs and levels of pollution they create; they have different efficiencies in power generation and related problems. It is then up to ‘society’ to make a choice about how much power generation it wants and then address the various consequences.

Such an analysis effaces the nature of Australia as a capitalist society in a world-system of capitalist states, and thus does not see how the question of energy use is determined by the internal dynamics of capitalist competition and by class struggle.

The history of capitalism has been a history of the incredible and ongoing technological revolution at work and across society. These ongoing revolutions have been ones in relation to the use of energy.

We can say broadly there are three dynamics at play here. Firstly, there is the transformation in production, with an increased proportion of capital being spent on technology compared to labour. Secondly, there is the development of global commodity chains, of both inputs and outputs, and the speed that these move around the globe. And thirdly, there is the geography and organisation of what we might call ‘social reproduction’ — where workers live, where we travel, how we eat, get sick, celebrate, etc. An increasingly important component to all three dynamics is the mesh of digital technologies which coordinate production, organise logistics, and allow us to both consume and socialise.

What drives these movements within Australian capitalism? It is crucial here to consider the dynamics produced by competition between firms. All firms are disciplined by competition with each other. In general, they try to produce more productively and sell more cheaply than the competition. Those that don’t and become less profitable struggle to attract sales and investment and risk going out of business. This drives all firms to take on more technology to keep up and compete with each other.

Firms are driven to sell commodities as quickly as possible. The sooner a sale is made the sooner investment returns. The sooner investment returns, the sooner it can be invested again, thus delivering more profit within a given time frame. So too each firm wants to source inputs as cheaply and as quickly as possible, and to sell to as many markets as possible. This builds complex logistics networks across the planet – with all that involves.

But it is class struggle we are particularly interested in. At work, capital is driven to try to control labour as much as possible. In turn, we resist it and push for our own autonomy as much as possible. The technology used to organise the process of work is one of the weapons and terrains of this battle – from the conveyor belt to the digital-measuring of drink sizes in bars. The intensification of technology in the workplace is often an intensification of exploitation – of increasing the productivity and intensity of work. We also see this play out in the home and in our communities, taking the form of the second work-shift of reproductive labour and the expansion of digital media into all our lives.

It is these dynamics that lie at the core of the question of energy use in a capitalist society, and which play themselves out in energy production as an industry. Traditionally energy production (in the form of coal or nuclear power) have been sites of intense capital investment. The ratio of capital to labour is very steep. In a real existing capitalist society, where capital moves from industry to industry and prices fluctuate, firms accumulate profits through exploitation, and they do so in proportion to the size of capital invested. Nuclear and coal plants have functioned as huge sinks of profit accumulated from workplaces across the economy. Through the ownership of stocks and bonds in these firms, these profits are then distributed across the capitalist class (and into our super funds….) Just as their product – electricity – is a key (if not the key) input for that economy, its price plays a highly determinative role in the movement of prices as a whole.

The control of energy inputs - oil, gas, coal, uranium, etc. - also gives firms and states tools which impact the operation of investments and accumulation across the globe. Tools which are essential to the exploitation of labour. The violence of the global order of capitalism cannot be explained without grasping this..

The shift to renewables, offers a challenge in at least two ways. After construction costs the costs of running renewables can be almost non-existent. This means these producers can sell energy much more cheaply into the system, cheaper than coal or gas can produce, and thus compelling the latter to sell energy as cheaply and thus less profitable and potentially rendering the value of the capital invested in them worth less if not worthless. Also the lower volume of capital invested in renewables means a lower total mass of profit returned. We suspect it is these destabilising potentials which in part explain capital’s ongoing inability to meaningfully move to renewable energy - because it is not primarily a technical question.

b) What is a ‘Labour Crisis’?

Increasingly, the mainstream media reports that there is a shortage of workers.

Large areas of Queensland have been identified as sites for significant renewable investment in solar and wind generation. This poses a challenge of who will build both the solar plants and the necessary infrastructure For example the Copperstring 2032 project involves the construction of transmission lines from Mount Isa to the East Coast. The ABC reports that it has been a struggle to hire the 800 workers needed for construction.

Similarly, the Clean Energy Council reports that, on a national scale, 250,000 to 400,000 workers will be needed over the next 15 years if Australia is to start exporting energy and ‘green hydrogen’. (ABC News, 2023b) The idea that Australia might replace coal exports with renewable energy exports like hydrogen is key to the various energy transition plans for capital developed by business leaders, environmental organisations and unions. This would allow Australia to maintain its position with the world-system of capitalism. (MacFarlane, 1977)

Commentators see that the only way this can be filled is via immigration. However, there are also concerns that the regions where workers need to be located don’t have the facilities, logistics and infrastructure to support these populations.

What do we make of this? To answer this we need to examine what a labour crisis is.

A labour crisis means that there aren't sufficient numbers of people with the skills, willingness, and capacity to be employed at the level of pay for profitable investment to proceed. This is a general concern for capital, but a specific one for capitalism in Australia. Social peace in Australia has largely been undergirded by the racist White Australia Policy and its descendants, where the supply of labour is limited to keep wages at a level conducive to social stability. The history of capitalism in Australia is a history of the contradiction between the need to keep this peace and the desire to expand the pool of labour.

One of the problems for capital is workers’ lack of willingness to uproot their lives and move to regional Queensland. It is important to recognise this as a form of class struggle, wherein workers insist on being more than just a body carrying the capacity to work; to be sold as the market desires. The mining boom addressed this issue with FIFO workers, paying high wages and the costs of flying staff in and out of regional worksites on an ongoing basis. An effect of this was it pulled in workers from other industries and pushed up their wages. This led to the concern about the rise of a ‘two-speed economy’.

We speculate there are two reasons this can’t be replicated in the renewables industry. Firstly, currently profitability is not high enough to handle the elevated wage bill and transport costs. Secondly, the construction work is far more reliant on qualified electricians – but the work offered is less interesting and appealing than in other industries, and potentially undermines prospects for ongoing career development.

c) Environmental context

“To develop the continents, the seas, and the atmosphere that surrounds us; to “cultivate our garden” on earth; to rearrange and regulate the environment in order to promote each individual plant, animal, and human life; to become fully conscious of our human solidarity, forming one body with the planet itself; and to take a sweeping view of our origins, our present, our immediate goal, and our distant ideal — this is what progress means.” – Elisee Reclus, Progress (1905)

To this point, we have discussed energy production in much the same way as we would any other commodity. Ultimately, however, the question of how energy is produced is one which calls into question the continued survival of human civilisation. As this bulletin is being prepared, the globe has just experienced the hottest week ever recorded, and as things stand, we are speeding towards the tipping point of a 2 degree Celsius rise in global warming. This looming catastrophe has driven left wing parties around the world to formulate programmes which they claim can avert the climate crisis: thus, the likes of the Green New Deal and calls for a Green Industrial Revolution.

The most obvious barrier faced by such models is the entrenched power of the fossil fuel industry — not only as a segment of capital in itself, but as one which literally powers the rest of the capitalist economy. The more serious advocates of these programmes are willing to concede that this poses serious obstacles to implementation. What is almost always ignored, however, is the invisible barrier which really dooms the social democratic vision of a reformed, green capitalism: the inherent logic of capital accumulation.

The ongoing reproduction and stability of the capitalist mode of production depends upon satisfying a never ending, and ever expanding, compulsion for growth. Without growth, capitalism is thrust into crisis. Energy use is coupled with growth. And as an important recent study by Lorenz Keyßer and Manfred Lenzen notes, “there is no empirical evidence for the possibility of an absolute decoupling between GDP and aggregate material use”. Reduction of the latter is, they point out, “central for climate mitigation, the reduction of environmental impacts and prevention of biodiversity loss.” (Keyßer & Lenzen, 2021) Claims that absolute decoupling can be achieved rely on a nationalist means of accounting. Brockway, et al. tell us that such decoupling can only be observed “at the national level”, in a “limited number of countries (e.g., the UK and Denmark)”, and “for relatively short periods of time.” For the most part, what is actually being measured in such examples is the offshoring of domestic manufacturing. (Brockway, Sorrell, Semieniuk, Heun, & Court, 2021)

Keyßer and Lenzen also note that production of renewable energy has “a considerably higher material footprint than fossil fuels”, which raises the prospect of metal supply shortages and conflicts with local communities over material extraction processes – particularly in the Global South. Their research suggests that sustainability requires that “the global material footprint…be significantly scaled down, to ~50 billion tonnes per year…which is highly unlikely to be compatible with growing GDP.”

Frameworks which assume a consistently, and permanently, rising GDP only face further problems from there. A transition to a renewable energy system would likely see a substantial reduction in returns on energy (Energy Returned on Energy Invested; EROI), limiting growth. It is highly questionable that, in such conditions, renewable energy could meet the continually expanding demand for output.

Nicholas Beuret’s critique of the climate agenda proposed during Jeremy Corbyn’s reign as leader of the Labour Party lays out the data in stark black and white: for the UK (the rest of the world put aside) to achieve just one of the Labour-Left’s more modest goals — meeting electric car production targets by 2050 — would require doubling global production of cobalt, utilising the entirety of the worlds production of neodymium, using three quarters of the worlds lithium output and nearly a third of global tellurium, and half the world’s copper production. As he concludes, “there is simply not enough raw material to go around, and it is currently not being produced fast enough.” (Beuret, 2019)

All of this resource extraction is carbon intensive. As is this steel and concrete infrastructure which accompany such plans. As Jason Hickle and Giorgos Kallis have noted:

“It is true that different materials have different impacts, and that renewable and non-renewable materials have different kinds of sustainability thresholds… [but] because all materials have some impact, indefinite growth of any material category is not compatible with ecological principles.” (Hickel & Kallis, 2019)

The upshot of this is that current energy consumption, continuously compounded by a receding horizon of infinite growth, means a global green transition which itself destroys the environment. (Beuret, 2019; Bernes, 2019) It means an Earth which is stripped bare of all necessary minerals, and heavily polluted in the process. A study produced by the Dutch Energy company Metabolic, in cooperation with Leiden University, bluntly begins by stating that “The current global supply of several critical metals is insufficient to transition to a renewable energy system.” (van Exter, et al. 2018, Fig. 1) Under capitalism a green transition is ultimately guided by the needs of capitalist production and consumption, not ecological sustainability and meeting human needs.

It follows that any serious consideration of transition-feasibility — i.e., the speed and extent to which fossil fuels can be replaced with renewables, — must take into account the relationship between a given proposal and the likely effect on capital accumulation.

Fig 1.

In writing about Green New Deal proposals, Matthew Paterson points to an obvious contradiction: more growth means cuts to emissions have to be made faster and more extensive. A target of cutting 3% of emissions per year in a country experiencing growth of 2% faces a real annual target of around 5%. “To illustrate the scale of this challenge”, Paterson writes, “historically, emissions have declined relative to GDP by only about 1% per year, in the aftermath of the 2008 recession.” (Paterson, 2019)

One aspect of this contradiction which has not received enough attention is the phenomenon of ‘rebound effects’ produced by energy efficiency. As Brockway, et al. put it, “the evidence suggests economy-wide rebound effects” (which include increasing consumption) “may erode more than half of the potential energy savings from improved energy efficiency” and that “the models used by the IPCC and others take insufficient account of these rebound effects”. (Brockway, et al., 2021)

Despite this, the need to maintain growth is assumed by every major proposal which governments and international agencies like the IPCC are willing to consider. What do they envision a green transition within capitalism looking like? The trick which allows IPCC modelling to project successful limitation scenarios of 1.5 degrees is the unquestioned assumption that negative emissions technologies will be developed which are capable of removing between 100 and 1000 billion tonnes of carbon dioxide between now and the year 2100. These negative emissions technologies (or NETs) require bioenergy carbon capture and storage methods (BECCS) and the widespread application of afforestation (the introduction of trees to previously unforested areas). All scenarios assessed by the IPCC which fall within the 1.5 degree scenario rely completely on the sustainability and feasibility of NETs.

The truth is that NETs like BECCS are extremely controversial among climate scientists and there is good reason to believe that reliance on them is not viable. As such, mainstream modelling must be read as artificially doubling the size of our ‘carbon budget’ for remaining within sustainable bounds. (Keyßer & Lenzen, 2021) The runway we have left is even shorter than it appears at first glance, and our current trajectory is towards an apocalyptic warming of over 4 degrees.

Putting aside questions of technical feasibility, it must be added that the EORI of NETs is extremely low. Furthermore, reliance on NETs would necessitate an enormous change in land and water use, which, if not properly managed, would pose threats to biodiversity and food security. All of this makes their effective utilisation within capitalism highly dubious. As we have pointed out in regards to the raw materials for renewables, the most likely victims of an expanding scramble for land and water resources would be the Global South.

The problem of space is a constant theme in the renewable energy literature — according to environmental scientists like Vaclav Smil, current consumption levels in the United States (which would only expand with continued economic growth) would require dedicating between 25-50% of the nation’s land mass to energy production. (Bernes, 2019) What effect would such a transformation have on the prospects for profitability? As we documented in the first issue of this Bulletin, “Carbon storage and biofuel production are viewed as competitors in the market for land-use”, making them a threat to existing agricultural production. Citing projections by the Australian Department of Agriculture, we noted that even with rapid climate action, profits in agriculture would fall by between 2 to 31.9% by 2050. The more likely scenario of “limited action” raises that to up to 49.9% — and even higher in livestock. (Class and Capital in Australia, 2023)

What does this do to food security? The current outlook is already bleak. A recent paper published in Nature Communications suggests that prior research has likely underestimated the risks of ‘synchronised low yields’ among the world's breadbaskets – in other words, that the growing risks of large scale, climate-induced crop failure, posing systemic risks to global food security, is even higher than we thought. (Kornhuber, et al. 2023)

Dr. Stephen Hatfield Dodds, who had advised the Victorian State and Albanese governments on the environmental impact of economic policy, has similarly been guilty of proposing ‘green growth models’ which fail to account for both natural and economic limits. His modelling suggests the potential for an ‘absolute decoupling’ between material consumption and GDP in Australia, but this has not stood up to scrutiny. (Hickel & Kallis, 2019) James Ward, a Senior Lecturer at the University of South Australia, notes in his analysis of Dodds’ model that:

“Permanent decoupling (absolute or relative) is impossible for essential, non-substitutable resources because the efficiency gains are ultimately governed by physical limits… non-substitutable resources such as land, water, raw materials and energy… are ultimately governed by physical realities: the photosynthetic limit to plant productivity and maximum trophic conversion efficiencies for animal production govern the minimum land required for agricultural output; physiological limits to crop water use efficiency govern minimum agricultural water use, and the upper limits to energy and material efficiencies govern minimum resource throughput required for economic production.” (Ward, et al., 2016)

Ward proceeds to use Dodds’ data to project energy consumption in 2100 being five times higher than in 2015, with material extraction increasing by 71%. (Ward, 2016, Fig. 2) What energy sources will fuel this massive looting of the Earth’s resources in the process of transition? Which communities will suffer at the hand of extractive industry, so long as the tools for digging up this raw material remain in service of profit – whatever the human cost?

Fig. 2 (a) GDP, (b) final energy demand, and (c) material extractions

It is highly unlikely that NETs will play a substantial role in the necessary transition to renewables. These are the only proposals developed by proponents of Green Growth (including the IPCC) which project the possibility of staying under 2, let alone 1.5, degrees of warming. Scenarios modelled by the IPCC which don’t rely on NETS fare little better in terms of feasibility, and drastically reduce the time-frame for effective action. The course we are currently on, largely dictated by the power of fossil capital, but ultimately constrained by the imperatives of capital accumulation itself, renders this a roadmap into the abyss.

Serious projections must assume low energy-GDP decoupling and an extensive period of transition to renewables. In Keyßer and Lenzen’s study, the only scenarios modelled which meet this criteria, making it possible to stay below 1.5 degrees, are those which remove economic growth as an imperative; which is to say, scenarios which assume the overthrow of the capitalist mode of production. (Keyßer & Lenzen, 2021)

“Have the factory and the workshop at the gates of your fields and gardens… Not those factories in which children lose all the appearance of children in the atmosphere of an industrial hell… factories in which human life is of more account than machinery and the making of extra profits… factories and workshops into which men, women and children will not be driven by hunger, but will be attracted by the desire of finding an activity suited to their tastes, and where, aided by the motor and the machine, they will choose the branch of activity which best suits their inclinations…” - Peter Kropotkin, Fields, Factories, and Workshops (1912)

7. Appendix

a) Surface conditions of Capitalism in Australia

Once again, if we look at the surface phenomena of capitalism in Australia, we can see in broad outlines the general contours of its conditions. (Reserve Bank of Australia, 2023)

The overall tendency is that accumulation holds but is slowing. The cost-of-living pressures are biting, but simultaneously the demand for labour is high. Inflation outstrips wages. Housing remains a particularly dense knot of contradictions as interest payments, house prices, and rents rise together. The impact this has on consciousness remains complex and contradictory.

It is argued that both are expressions of a global condition of over-accumulation of capital, but more work is necessary to demonstrate this connection both empirically and theoretically.

Growth is low – predicted to be 1% by the end of year.

RBA reports business investment intentions have slowed. Resource investment is being buoyed by export prices. Smaller business are reducing investment plans as the cost of credit rises

Inflation is high, but growth in inflation is slowing, currently at approx. 6%.

RBA reports that business sees input cost rises as slowing and prices rises are also slowing.

The labour market remains tight – unemployment is at a near 50 year low of 3.5% (3.7% at time of writing.)

The underemployment rate, however, is at 6.5%.

The labour participation rate and Employment to Participation rates are at their highest rate ever (67% and 64.5% respectively).

The RBA reports business intentions to maintain or increase employment.

Wages continue to grow, albeit at a slower rate, in June quarter 2023, the seasonally adjusted WPI rose 0.8% for the quarter and 3.6% over the year.

This growth is not keeping up with inflation, Real disposable income is 4% lower than a year ago.

Household consumption has slowed since mid-2022, average growth is .25% in recent quarters.

Household prices have started to increase again at approximately 1% a month, following an 8% decline since the peak of April 2022.

Rental vacancies remain low and rents have risen over 10% in the first two quarters.

b) Text of Renewable Sector Questionnaire

The following set of questions are aimed to help understand the conditions for workers in the renewable energy sector. Renewables are of increasing importance to the Australian and global economy, they are ‘the future.’ But the sector is still relatively underdeveloped. Renewable energy companies are subject to the whims of various governments, an unstable and cutthroat market and the risk of experimental technologies. How workers bear the results of these pressures is of particular interest to Class and Capital in Australia.

Class and Capital in Australia are a small group of workers attempting to understand the functioning of the Australian economy and its implications. Our questionnaires help us tease out the connections between what's happening in broad economic terms and how these things affect workers. If you’re interested in answering our survey you can rest assured any answers will be anonymous (unless you want them to be public!) and we will make sure you can’t be identified. Feel free to answer as many or as few of the questions as you want and give as little or as much information as you're willing to share. We appreciate anyone taking the time to engage with us.

What sector of renewable energy do you work in? (ie solar, wind, hydro)

What is your job? (trade, management, admin, labourer etc)

How long have you worked in the industry?

How old are you? Where are you from?

What did you do before your current job?

Have you worked for other companies in the industry?

Are you directly employed? Or do you work through an agency or subcontract?

How many people do you work with?

What are the ratios of labourer-apprentice-qualified tradie at your company?

What does your normal work day look like?

How do you feel about your work? Is it rewarding, fun, stressful, long, repetitive or interesting?

Do you find your job meaningful? What do you like/dislike about it?

Does your job provide a good quality of life? Why or why not?

Do you think your pay and conditions are fair?

Does your company provide all the tools and materials you need to do the job?

Are there other things your company should provide but doesn't? Do you cover them yourself? For example do you use your own car, pay for fuel out of pocket, use your own mobile phones etc.

How much does your job require digital administration? Do you do this on your own devices or company provided ones? Such as a laptop, ipad, or phone. Do you find yourself doing this work ‘out of hours’?

Do you think your company makes much profit? Is that reflected in your pay and conditions?

Do conflicts ever come up at work? Do you and your colleagues talk about them? How are they resolved?

What does the management chain at your work look like?

Who deals with health and safety in your workplace?

Are you a union member? Have you ever been before?

Do you worry about your trade being protected? Does automation or the use of unskilled labour mean less hours or a lower quality of work?

Does your company provide education and training?

Have you gained any qualifications from working in Renewables?

Do you think you’ve gained skills that will translate into other industries?

Do you see yourself continuing in your role for a long time?

Have you worked interstate since working in the renewable sector? Did you notice anything significantly different?

How does working in Renewables compare to say, construction, industrial or residential?

Did concern about climate change influence you into working in Renewables?

Do you think there are ways your job could be done more efficiently?

Do you think the way the industry is organised makes sense? What needs to be invested in? What needs to change?

OPTIONAL: If you're comfortable with us using your name or any other personal details about where you work feel free to enter them here

OPTIONAL: Please leave any other feedback or thoughts!

c) Sources

Dave Eden, ‘Sunburnt Country: Australia and the Work/Energy Crisis’, pp. 281-294 in Commoning with George Caffentzis and Silvia Federici (eds. Camille Barbagallo, Nicholas Beuret, and David Harvie), 2019

Recharge News, Vestas says worker injured at Australia's Macarthur wind farm, 2012

Wind Power Monthly, Second worker injured on Macarthur project, 2022

Worksafe NSW, Fatal fall while installing solar panels, 2018

Michael Bloch, Solar Installer Rooftop Safety Spotlight In SA, 2022

Safework, Electrical apprentice falls from roof during solar installation, 2022

About Regional, Wind farm worker loses hand in workplace accident, 2021

Joshua Treisman (Ibis World), Blowing in the wind: Decreasing wholesale electricity prices have reduced revenue, 2023a

Joshua Treisman (Ibis World), Watts Up: Government Support has Fueled Ongoing Revenue and Generation Capacity Growth, 2023b

International Energy Agency, Special Report on Solar PV Global Supply Chains, 2022

McKinsey & Company, Renewable-energy development in a net-zero world: Disrupted supply chains, 2023

China Labour Bulletin, For China’s workers, the boom in clean energy comes at a cost, 2019

AEMO, AEMO CEO speech at Australian Clean Energy Summit 2023, 2023

ABC News, AGL, Origin announce upcoming energy price rises for households, small businesses, 2023a

Stanwell, Whats Watt: What are the main costs behind your electricity bill?, 2022

ABC News,'Daunting shortage' of skilled workers looms over giant, renewable energy projects, 2023b

Bruce MacFarlane, ‘Australia's Role in World Capitalism’, pp. 32-64 in Australian Capitalism: Towards a Socialist Critique (eds. John Playford and Douglas Kirsner), 1977

Nicholas Beuret, A Green New Deal Between Whom and For What?, 2019

Jason Hickel & Giorgos Kallis, Is Green Growth Possible, 2019

Jasper Bernes, Between the Devil and the Green New Deal, 2019

James Thomson (IBIS World), Coal Mining in Australia, October, 2023

Profit is a key concept for our analysis. Indeed, we hold that profit, derived at its base from the exploitation of labour, is the driving rationale of capitalist firms and system, and the overall determination of the health of both. Especially important for us is the argument that the average rate of profit, created in part via the fluctuations of prices and the movement of investment, is the deep process that underscores capital’s wellbeing. The rate of profit and the average rate of profit are abstract concepts that try to grasp the relationship of the proportion of capital invested in labour to capital on a whole.

But actual capitalist firms don’t see either. They see profit as the relationship of the excess of sale price to cost/money invested on a whole, or the return on investment in relation to financial instruments. Decisions on investment are made by comparing the potential profits on where capital can be invested (sunk costs also considered).

We are struck by AEMO’s words as the profit in renewables appears considerable. However, compared to other industries, keeping in mind the size of investment, and the time it may take to see returns, it seems not to be at a significant enough level to compel capitalists into action.